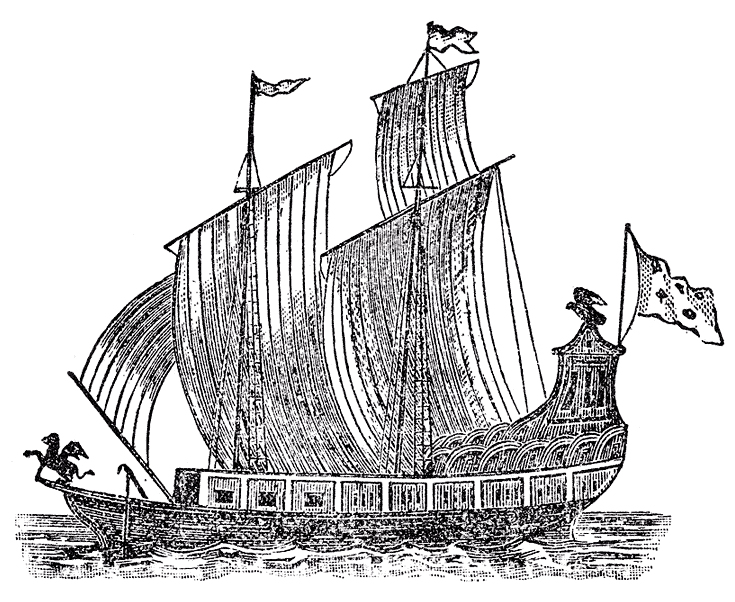

The French explorer LaSalle entered a large body of water from the straits known as “Detroit,” on August 12, 1679. He named the lake, “St. Clair,” after Saint Clare of Assisi, the Roman Catholic patron saint of fair weather. He was traveling in Le Griffon, the first European-styled ship built in New France and the first European ship to sail west of the Niagara Falls. And like much of European culture, the caravelle design was remodeled somewhat to withstand ice and haul extensive freight. In a sense, it was the first “freighter” to sale the Great Lakes.

LaSalle, like other French explorers, was navigating the area of North America claimed by the French in hopes of identifying a route to the Pacific Ocean. What they found, ultimately, was the Mississippi River, and a route to the Gulf of Mexico. Instead of gold, which the Spanish plundered in Mexico, they found an abundance of beaver — prized for hats and garments — and timber.

Unfortunately, the Le Griffon falls into the category of maiden voyages gone bad. It made its way to the mouth of Green Bay in modern Wisconsin and disappeared on its return trip with 6,000 pounds of beaver pelts. Great Lakes researchers Steve and Kathie Libert, and their company Great Lakes Exploration Group, LLC, have spent 20 years trying to prove that the Le Griffon sank among the Huron Islands. This year they published Le Griffon and the Huron Islands, with Mission Point Press.

“For 342 years these islands have held the secret resting place of the Holy Grail of the Great Lakes.”

Hundreds of ships have sunk in the Great Lakes since that voyage, captivating the imagination of shipwreck hunters. I wrote earlier about a book of poems, Harborless, written by Cindy Hunter Morgan, which created impressions from the loss of several vessels. But the uniqueness of this one, its historical connection to the early exploration of the Great Lakes region, and the story of Steve Libert make it a worthwhile read. Libert became intrigued “by the mystery of the ship’s demise as an eight grade student in Dayton, Ohio — a long ways from the Great Lakes. “My interest began the day my teacher reached over and touched my shoulder and said out loud in class, ‘Maybe one day someone in this class will find it.’”

As researchers, the purpose of the book is to document their assertion of the “correct” geographic location where the ship sank, the building methods used in 17th century French ship construction, and assembling supportive cultural materials. In addition, the book reveals the location of the huron Islands where Libert believes the ship went down, and “the exciting discovery of a colonial-age shipwreck, precisely where historical documents place Le Griffon’s final moments.” He stops short of identifying the shipwreck as Le Griffon, but the implication is there.

“Le Griffon ended her maiden voyage among these beautiful islands. The confusion as to where these islands were located in present time added to the mystery of the legend. Some historians believed they were in Lake Huron, others in the Beaver Island chain in Lake Michigan.”

Allen Pertner, a shipwreck interpreter, in an analysis included in the book, said Le Griffon was “a new ship for the New World. I see in her what I take as provisions for surviving ice…This wreck has a lot to say and we should listen. If ever there was, this is the time when we need to remember what (J. Richard) Steffy wrote: ‘Research and reconstruction are contributions, recording is a debt.’”

Post written by Dennis Archambault

Woodcut of Le Griffon/Wikipedia