I was struck by this headline in a Twitter feed: “How journalists can become cartographers and track the impact of the climate crisis.” It referenced an article published by the Reuters Institute, University of Oxford, in May 2021, suggesting that reporting on climate change can map out the regions where climate change is occurring. Journalists contribute to “cultural mapping” through the description of locales that their subjects are found, as well as the cumulative effective of the references. There is an actual category of “journalistic cartography,” but that is a more literal application of graphic illustration of ideas.

Several years ago, I was struck by the growing use of cartography to illustrate conceptional regions. My understanding of map-making was ignorantly based in grade school geography class. In this case, the cartographer was discussing “food deserts.” I’m reminded of my fictional model, Fra Mauro, and his cultural mapping of the world that he was known to chart in the traditional sense.

The Third Coast has national boundaries as well as natural coastlines, or points that jut out. It’s also a “coast of nowhere.”

I began a search to learn more about how journalism, especially good travel writing, create a sense of place, thereby mapping the region with a kind of cultural overlay. I came upon “Pei Yun’s Process Journal,” from the NTU School of Art, Design & Media – Final Year Project. His topic: “Cultural Cartography.” Yun’s journal drew some interesting references from Mapping Reality: An Exploration of Cultural Cartographies, by Geoff King:

- “The fictional, once mapped, may become real.”

- Maps can overpower the boundaries of a territory, in which cartography represents the map similar to its scale of empire.

- “No existence is possible on unmapped ground. Cultural groups create their own mappings, imposing them on and writing them into the territory itself in a way that undermines the distinction between map and territory.”

- “The worlds we inhabit are largely cultural rather than natural and as such are subject to a wide variety of cartographies. None of these is fixed on any ultimate or transcendent ground.”

What’s very interesting is the observation that a map is seen as a “communication channel” for information transmitted from one place to another.” In this context it’s a medium, not a static document. What’s even more fascinating is that “data are to be taken from the real world before being encoded in map form and then decoded by the map user.”

Yun’s journal then goes on to discuss migratory maps, as the cultural migrations of this era are blurring identities of place.

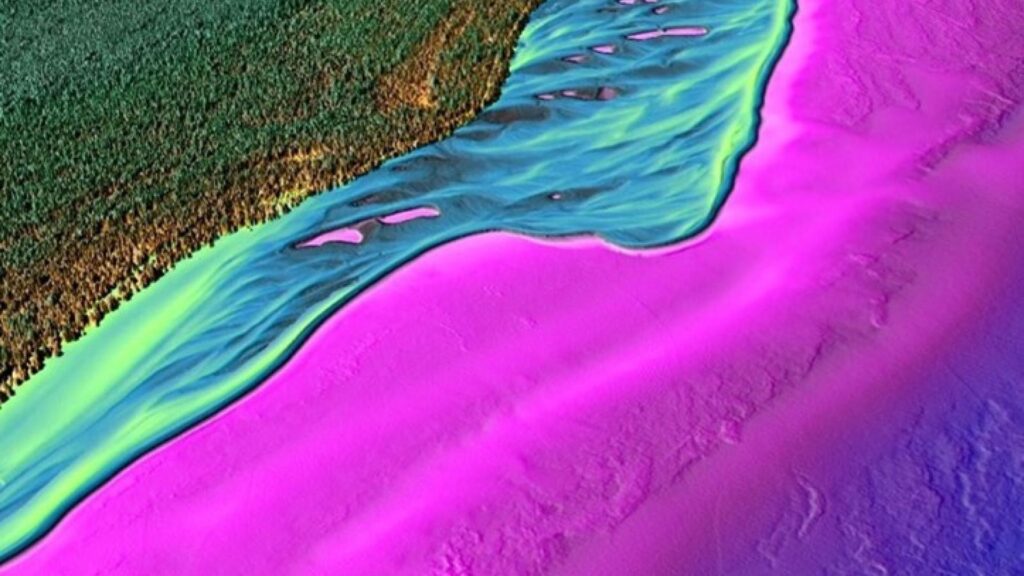

These elements are all relevant in the concept of the Third Coast. The cultural map can overcome boundaries of territory, just as a static image of a lighthouse in Duluth defines place through illumination and mounds of earth below the surface of the lake defines an ancient hunting ground. It is equally defined by the indigenous canoeist who traverses the lakes to define his people’s sense of place, not generally noted in travel maps. And then, the naturalist and environmentalist defines the coast with human inhabitants as perpetrators of destruction or agents of restoration – other creatures looking on.

And like John Hartig’s reference, we need to turn around and look at the water to understand this coast, which on occasional still days offers a reflection.

Post written by Dennis Archambault

Visual by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration