McCarty’s Cove lies at the foot of Michigan Street in Marquette, Michigan. It is a place where Glenn Stevens has found solace at various times in his life — a scene that is featured on the cover of his book of photographs, Michigan Street.

He returned to that place last summer when the world came to a stop during the coronavirus pandemic. The disruption of that moment and months of state lockdown, followed by periods of pause and multiple public health safety adjustments, was a time when nothing seemed to happen, yet a lot of profound things happened. It was a disorienting time that gave Stevens the urge to go.

Stevens is the executive director of MICHauto, an initiative of the Detroit Regional Chamber, which promotes development for automobile industry-related ventures and the future of the state’s economy. His work keeps him constantly moving. “I had been thinking about slowing down. Well, March of last year, I didn’t have a choice. The pause was unlike anything we’ve ever seen before, hopefully never again. My life literally ground to a halt, like everybody’s. We didn’t know what to do. It took me a while to adjust. We didn’t know what was going to happen.”

He drove from his home in Southeastern Michigan throughout the state, capturing images of places that are meaningful to him, keeping in mind his father’s advice: appreciate the sun’s presence before you, but look for how it illuminates what is behind you. It was one of those moments when, on the quiet shore of McCarty’s Cove, that gave Stevens an opportunity to reflect on what was behind him and what was ahead.

“I’ve always been a road trip type of person,” he explained. “Whenever I take a business trip, I always carve out a little time when I can go see something new…I’ll just get in the car and go. If I have time, I rarely take a direct route to where I’m going. I’ll take the back roads…heading in the right direction, but not always in a straight line.”

Even when you don’t know the destination, it’s good to stay off the highway and keep your eyes open and your ears open, listening and watching for what you may not be looking for.

“I like the northern part of our country and this continent,” he says. “I like the distinct four seasons. There are things that happen, like the trillium. It happens a certain time of the year then it goes away. It’s a sign, a physical sign of the seasons. It’s somewhat symbolic.”

During a period of death and misery among so many, compounded by civil strife and angry political division, Stevens found himself capturing the beauty of his state; along the water, and inland. But, invariably, it’s the water.

“Being on the water or near the water is very important to me, for a couple reasons: geographic change; it’s also very much a symbolic and psychological thing. A lot of people find the water a soothing, calming presence. I also believe in it as a life source. Fresh water is probably the most sustaining life source we have on this planet. I have a deep affinity for it. I grew up two blocks from Lake Superior. When you grow up on the big lake — gichigami (Ojibwe)– you appreciate it and I appreciate it even more today.”

When his journey took him to the end of Michigan Street, McCarty’s Cove, he experienced a unifying presence of mind, body, and spirit. “That cove is my special place on this planet. I sat there two mornings last year before the sun rose…I just sat on the beach, probably for 45 minutes and just looked out on the water watching the sun come up. I can’t tell you what that feels like. It’s just amazing. To see that, to feel that, to hear the water was good for the soul.”

Stevens is what one may call an amateur photographer — someone who makes photographs but doesn’t sell them or show them in galleries. But amateur too often discredits the artist. He assembled a collection of images that prompted his sister and one of his best friends to say he should sell them. He was encouraged to create a book, “but I didn’t have a purpose, a reason to do it.”

Then, a conversation with his church minister this spring led him to a men’s group focused on faith, family, and life. And there he met Manny Dines, a therapist who has worked with veterans and now suffers with ALS, Lou Gehrig’s Disease. The men committed to help Dines in various ways, looking for a way of helping him finance a van. Stevens worked his network among auto industry connections but came up short. He had one other thing to offer — a book of photographs. He has sold quite a few books to friends and strangers throughout the state and country, gained two major donations, and has begun placing the books in the few remaining bookstores in the state.

“I do have a deep faith, but I think we all have to work on our faith and this group of guys allowed me to do that. And I met Manny.”

Perhaps he met the reason for his journey.

“It was a quest to look at the priorities of our life, and this halt — not a pause happened…and I can tell you unequivocally that I would not have done all this. I wouldn’t have started meeting with these guys. I wouldn’t have done this book, if it wasn’t for that.”

Stevens started a website last year called “Michigan Street.” He recently updated it to reflect the book’s purpose, “Manny’s Machine.” As he notes on the website:

“In these trying times, or for that matter during any times, we also need to look out for each other and remember we never know what our friends, colleagues, or people on the street are going through. We all have to remember to pause, look around, look up and look forward.

“As the wise philosopher Ferris Bueller said, ‘Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.’”

To obtain a copy of Michigan Street, use this link: https://my.cheddarup.com/c/mannysmachine.

Post written by Dennis Archambault

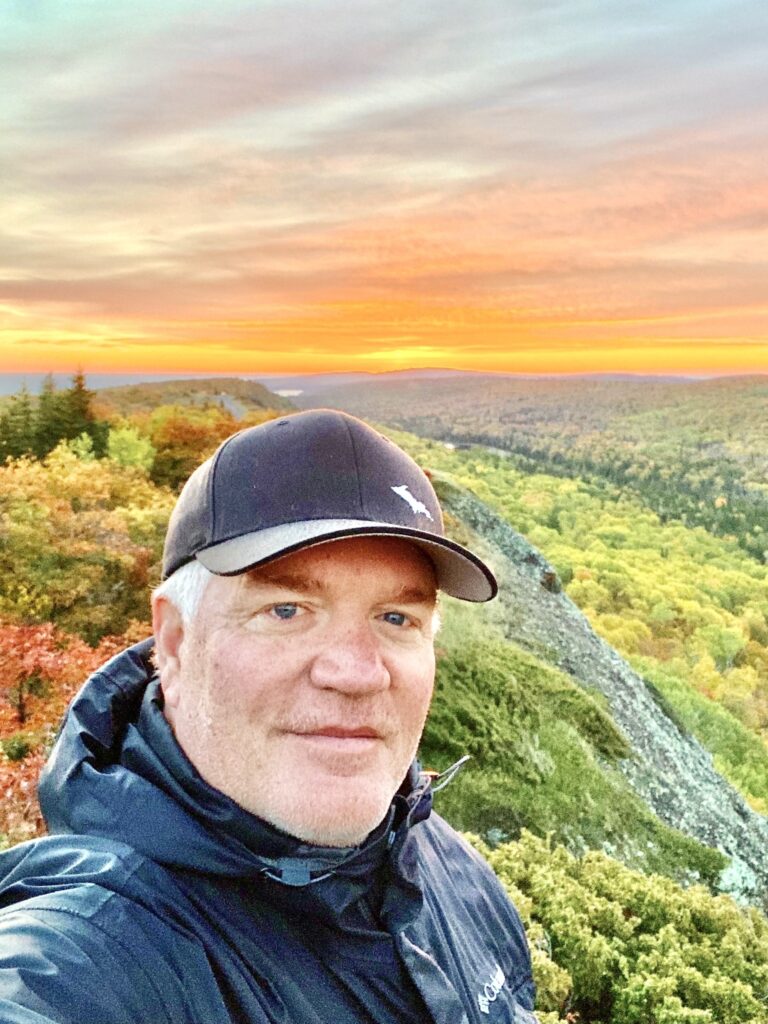

Photo by Glenn Stevens