On land surrounding the lakes there are four seasons, more or less. In some areas, spring is a split second and autumn extends long into November. In some areas winter is snowbound, cold, and dark for months. But there are really only two seasons on the lakes: in summer, the lakes are magnets for swimmers, boaters, anglers, and loungers. With the first furies of fall, the low-hanging gray clouds push us away, only to take a glimpse for fresh air, until the lake effect occurs.

I had never heard the term before, until I experienced the steady rains and snow of Cleveland and heard accounts of the large dumps on Erie and Buffalo. Living in Southeast Michigan, we may get a few good snowstorms each winter, but nothing compared to what I experienced in Cleveland.

In her memoir, “Lake Effect,” Linda Loomis writes, “Once the trees have dropped their leaves and autumn faces, Oswegonians (Oswego is located on Lake Ontario in New York State) brace themselves for the inevitable fury that follows. Our city is buffeted by prevailing northwest winds and buried annually beneath an average thirteen-foot snowfall…Meteorologists can explain it all now — ow the arctic air sweeps down from Canada and absorbs moisture from the warmer, open waters of Lake Ontario: how it arrives at shore saturated, shudders at the cold land mass, and drops the gray stalls of snow that have formed. There are other scientific details but what local residents know is the effect of the phenomenon. They see heavy snow-bearing clouds approaching and hurry out for the extra bread and milk, set shovels near the door, and check the fuel in the snow blower.”

Michigan author, Jerry Dennis, writes about lake blizzards in The Windward Shore: Winter on the Great Lakes. The word blizzard, he says, is derived from the reaction of German immigrants to such blinding wind and snow events during their first winters: “blitzartg,” or “lightening-like.” A few occur each year, defined by meteorologists as storms that have low temperatures, driving snow, and gale-force winds, thirty-nine to forty-six miles per hour. While attending Northern Michigan University in Marquette, Dennis recalled a particularly memorable one, which began eerily in the afternoon. The light, he recalls, “was soft and strange.” A television weather forecaster said, “Get ready folks. It looks like we’re in for a blinger.” In a matter of hours, he city became “erased by whiteness. Gusts lifted snow into marauding clouds that swirled down the street and eddied into the openings between the houses, building drifts that by morning would reach to the eaves. Then stronger winds funneled in from the lake, carrying snow in streamers so blinding we couldn’t see the houses across the street.” The wind over night “seemed to bellow with triumph.” By morning, classes were closed at the university and the state police had blocked all highways out of the city.

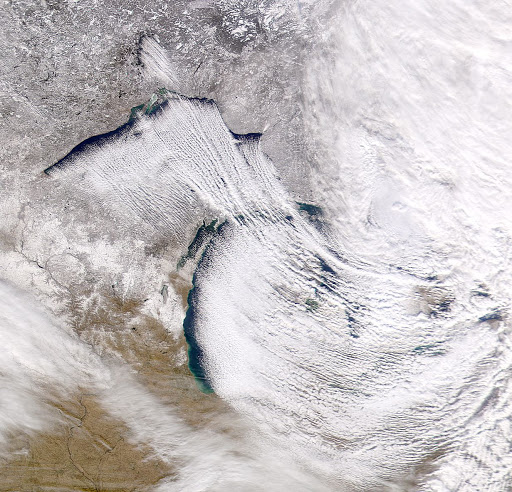

According to the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments (GLIA) center in Ann Arbor, major lake effect regions are the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and western coast of Ontario, the western coast of Michigan and the Georgian Bay region of Ontario, the southern edge of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. According to GLIA, climate change is increasing lake effect in these regions. “Warmer Great Lakes surface water temperature and declining Great Lakes ice cover have likely driven the observed increases in lake-effective snow. As global temperatures continue to rise and further warm the Great Lakes, areas in lake-effect zones will continue to see increasing lake-effect snowfall.” And as the winter temperatures warm, the snow that would have come to the southern Erie and Ontario coasts will turn to rain.

My lasting impression of lake effect snow is the great scene in Jim Jarmusch’s film, Stranger than Paradise, in which the characters Willie, Eva, and Eddie, find themselves on the edge of Lake Erie in a whiteout. With the wind howling, Eva says, “So this is it, Lake Erie?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eaYEHeseLog.

Blog written by Dennis Archambault

Photography credit: Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments