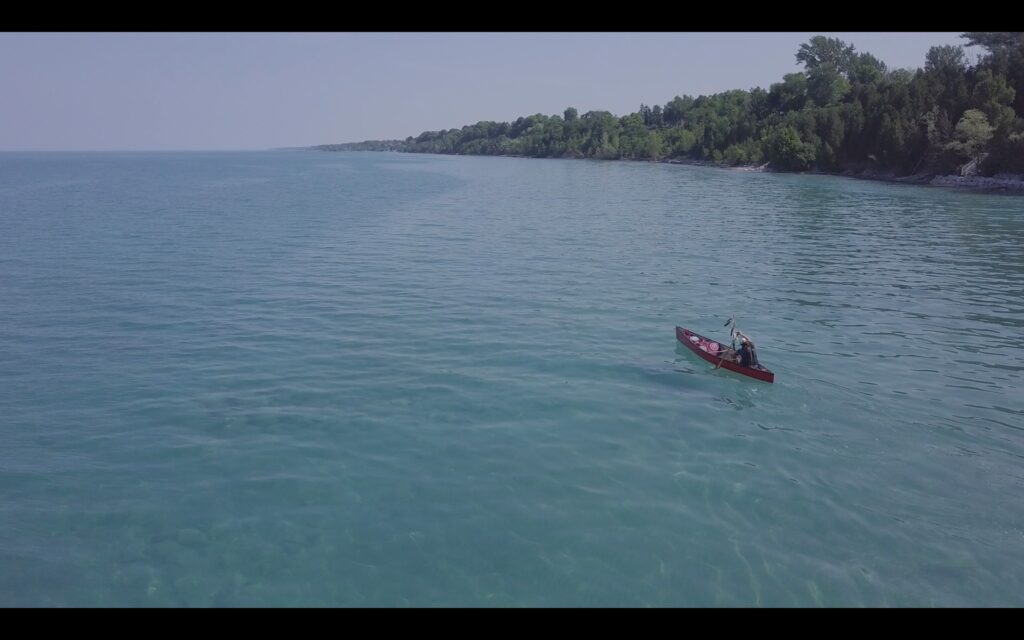

Studying the movement of water creates intelligence on multiple levels, believes Waasekom, an Ojibway activist from Ontario who completed a month-long journey this summer from the southern shores of Lake Huron, north around the Saugeen Peninsula into the Georgian Bay to draw attention to his culture’s presence and rights. Waasekom maintains a low profile, saying his role is to “hold space for others and for the voice of the water.” The water speaks of his ancestral past, the present and the precarious future. It is also what unites people in this part of the world — the Ojibway populations along the Great Lakes, as well as the Canadians and Americans on either side. Being present and mindful transforms the rowing process in a spiritual sense. Water, he says, is a “sacred commons.” He reminds us that these were the original highways that his people and the “settlers” who followed, took to get to their homes.

This was Waasekom’s third effort as part of the “Picking Up The Bundles” canoe journey. In 2017 he traveled from Duluth, Minnesota to Southern Quebec over 97 days. Supporters join him from the shore, rowing short portions of the trip. Otherwise he is alone. His agenda is to raise awareness of the failings of Treaty 72 (https://ammsa.com/publications/ontario-birchbark/saugeen-chiefs-mark-150th-anniversary-treaty-72) with the Canadian government. Among their grievances, the Ojibway ultimately want the rights to the lake bed, rivers, and streams, not just fishing rights. Control of the land below the water would give the First Nation a role in preserving the environment.

“Being on the water, watching the water moving, makes us intelligent and when we become intelligent we become well,” Waasekom says. “We become well by paddling, navigating on the water and in that wellness we become acutely aware and intelligent to everything that’s going on around us; the ways that the water moves, the ways that the wind moves to inform the movement of the water, all of the different kinds of winds and the different weather systems.” Focusing one’s consciousness of the water naturally draws you into thoughts about climate change and looking around you, you see “the way that the animals and birds are responding to that, and they have been for a number of years.”

Enduring the long arduous water trail is an allegory of the experience of indigenous people, says Waasekom. “We have to prove that we’ve never surrendered our occupation, our title; our title and our land use had to adapt to colonization. Eventually it became horse and buggy and eventually it became vehicles, but we’re still there. This was a way to look back at that time when our people traveled on the original highway and a way to look ahead to future generations. We’re putting an effort forward to let them know this is what we can do… this movement is a way… it’s not necessarily an activism. Being of that movement, studying that movement, being present with that movement, it puts us in that space, with that intent, with that context, so our movements become metaphors for the state of our people, the state of the planet, the state of relationships that existed… What we saw was the settler relationships and the ways that they accessed the water in contrast to the birds that only take what they need. You have all of these people who are developing the shorelines in multimillion dollar second and third homes, based on recreation, based on privileged enjoyment.”

The final day, July 4, was especially poignant.

“That day we were almost taken quite a number of times. We were getting discouraged. The waves were getting progressively more and more powerful. We were experiencing the water in its fullest glory… the full expressions of the lake itself. It was really challenging physically. By the last day we were worn out, generally, and we literally couldn’t even stop to check our phones and let people know that we were going to be late. We were afraid we would become completely enveloped by that water. We had to negotiate every little moment. This has never happened to me before where I was getting to the point that I was afraid that we were going to go under. For that to happen so many times in one day — all of sudden it became really emotional. We realized how much our people did to hold on to what we have, to where we could even make these claims, to be strong in our own homeland. A lot of sacrifice was given. There has been a lot of resistance, and that’s growing. In order to change this whole situation, we realize it’s not sustainable. We’re actually destroying the planet. We need to listen to indigenous people. We need to recognize their place. That’s what we’re finding. People are starting to come around to that… It showed us just how much love and strength that people had so that we can be here today. Also sending that out into the future for our people and how much it’s going to take to reclaim what we’ve lost. It’s going to be a fight. It’s going to be like being on that water. We have to be strong enough and brave enough and not give up and keep going. That’s what that last day was about.”

“Being on the water, watching the water moving, makes us intelligent and when we become intelligent we become well.”